Twin brothers Kip and Koby McClelland have both pursued careers in aviation maintenance. [Les Abend]

Knock on wood: I’ve been fortunate not to have experienced an in-flight mechanical event of any consequence with any of the airplanes I’ve owned. Until recently. And despite the seriousness of the event, the aftermath included positive aspects.

With my Piper Arrow loaded to its full capacity of four people (including me, two journalists, and an environmental executive director), the Lycoming IO-360 engine decided it no longer wanted to participate at full power. Instead, the engine protested by shaking the airplane with a pronounced vibration barely five minutes into the climb out. As though to scold me, the digits of the engine monitor display began to flash high EGT and high CHT numbers on the number-3 cylinder. I cringed.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowAlthough I would find out later that the damage was done before I reduced power, it seemed an appropriate course of action. Having contacted Jacksonville Center for flight following just moments prior, I informed the controller that we had an engine problem and would be returning to our nearby departure airport of Waycross (KAYS) in central Georgia. The controller seemed indifferent to our plight and simply acknowledged my intentions, instructing me to squawk VFR.

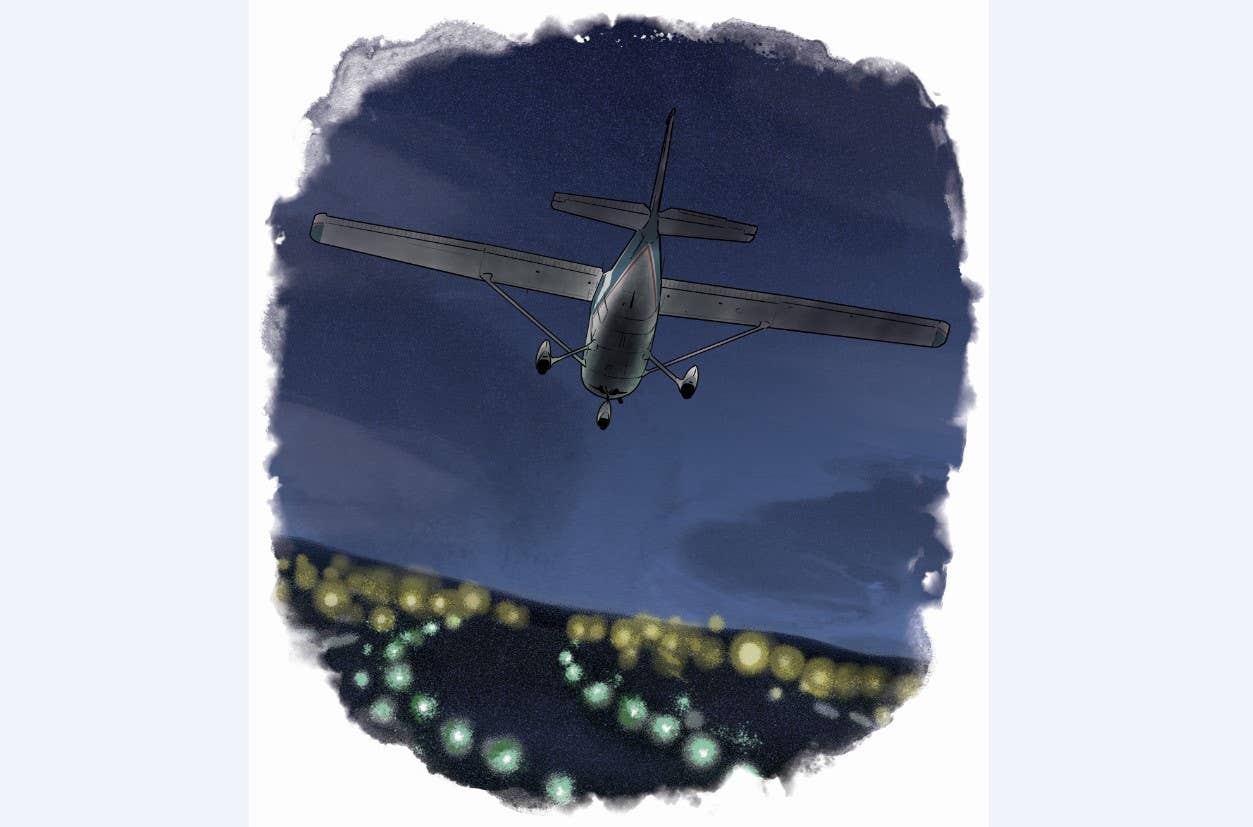

Meanwhile, passenger intercom chatter had gone silent. In my best airline captain voice, I informed my passengers that we would be returning to the airport out of an abundance of caution. Limiting my use of the throttle in the descent while pointing the airplane directly at the runway threshold, disregarding any semblance of a normal traffic pattern, we arrived back on terra firma without incident a mere 10 minutes after takeoff. I apologized for the abbreviated flight. The passengers responded with gratitude, grace, and understanding.

Taxiing toward a parking spot, I inquired via the unicom frequency as to the location of the maintenance shop. The reply: “We don’t have a maintenance shop on the field, but I’ve got a couple of numbers for local mechanics.”

Having failed my policy of packing an overnight bag for such contingencies, I shook my head. The first mechanic said that he was no longer operating freelance and had taken a full-time position for a flight department in St. Simon’s Island. Despite his new employment, the mechanic took 15 minutes to assist me in troubleshooting. The second call yielded a willing and able A&P, Kip McClelland, who offered up his more available A&P brother, Koby, but not before attempting to troubleshoot as well. Koby wasn’t available until late afternoon. Beggars couldn’t be choosers.

Following the troubleshooting guidance, I started the engine. A magneto check was normal, with the engine monitor indicating noticeably colder EGT and CHT temperatures on the number-3 cylinder. Toward the end of my engine run-up test, the pilots of a Falcon 900 crew parked nearby walked rapidly toward the Arrow. One of the pilots, who had an A&P certificate, described white smoke flowing out of the oil breather tube. Not good.

I called Savvy Aviation’s breakdown service for additional advice. With the footwork already accomplished in locating a mechanic, the phone conversation involved a final troubleshooting step, pulling the prop through a couple of rotations. This step revealed low compression, a symptom of a sick number-3 cylinder. The problem was becoming more expensive.

While commiserating with me, aspiring airline pilot and Marine vet James Kidd revealed that he was flying back and forth via a well-seasoned Cherokee 140 between Waycross and of all places, Flagler Executive Airport (KFIN)—my home turf. James was building flight time to qualify for a potential Spirit Airlines interview. He was departing shortly but would return later in the afternoon. Although my airline buddies had already promised a rescue flight, it was great to have another option.

Approaching noon, the very sympathetic and hospitable Waycross FBO staff offered me one of the crew cars. I sampled additional southern hospitality in the form of lunch at a local restaurant. Fried chicken isn’t high on my dietary list, but when in Waycross...

Koby McClelland arrived on the ramp earlier than promised. He had a cheerful demeanor as he described his troubleshooting plan of attack. A brief engine run-up, more white smoke, the removal of a very wet spark plug, and a borescope video revealed that the number-3 cylinder had experienced a destructive event. The valves were seated properly, but the top of the piston and cylinder walls indicated that something melted, most likely the rings. Great.

With cell phones to our ears, Koby and I shopped for refurbished cylinders. The task became problematic because of the apparent short supply. Fortunately, one shop could have a cylinder completed and shipped within the week, which I skeptically predicted would actually be the following week. Unfortunately, I was proven correct.

Another aspiring airline pilot, Zach Ballard, attempted to assist with temporary lodging for the sick airplane in one of the hangars in which his boss based a King Air operation, but the daily price offered was more conducive to tying the airplane down on the ramp. Shortly after my rescue posse arrived via retired United Airlines captain Kage Barton’s Mooney, the airport lineman who had been tolerating my tale of woe for most of the day offered an unoccupied T-hangar leased by a local pilot. The local pilot refused any compensation, not even a bottle of wine.

Once the new cylinder was installed, not quite two weeks later, I returned to Waycross with Kage and his Mooney. Knowing that I would be meeting Kip this time, I did a double take when he hopped out of the Cessna 150 he flew from his home base of Douglas Airport (KDQH). The McClelland brothers were identical twins with identical careers.

It wasn’t until that moment it occurred to me that I had met them both at another Georgia airport during a fuel stop where a faulty fuel servo that was later replaced was making my hot start technique irrelevant. The brothers offered diplomatic advice, which eventually got the engine started. Gotta be a small world when you meet twin A&Ps twice. The name on their company shirts should have clued me in: Twin Aviation Repair.

A former airline colleague, Boeing 777 check airman and designated pilot examiner Jay Smith, braved the one-hour mission home to Flagler with me, but not before we flew a 30-minute test flight, circling above Waycross Airport.

Savvy Aviation remained involved, analyzing data from the engine monitor. I was concerned that my operational habits led to the piston and cylinder destruction. It did not. An admired engineer friend noticed a slowly decreasing fuel flow in the data analysis graphs during the climbout. Combining that observation with finding no magneto, spark plug, or fuel flow issues, the most likely cause of cylinder detonation was momentary blockage of the fuel injector. An engine shop that I consulted agreed.

All things considered, the aftermath experience was relatively painless. Compassionate and accommodating people made the difference. That said, I could only imagine the possible outcomes had the intended environmental observation flight continued over the Okefenokee Swamp. Fortunately, the checkbook balance was the only casualty.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox