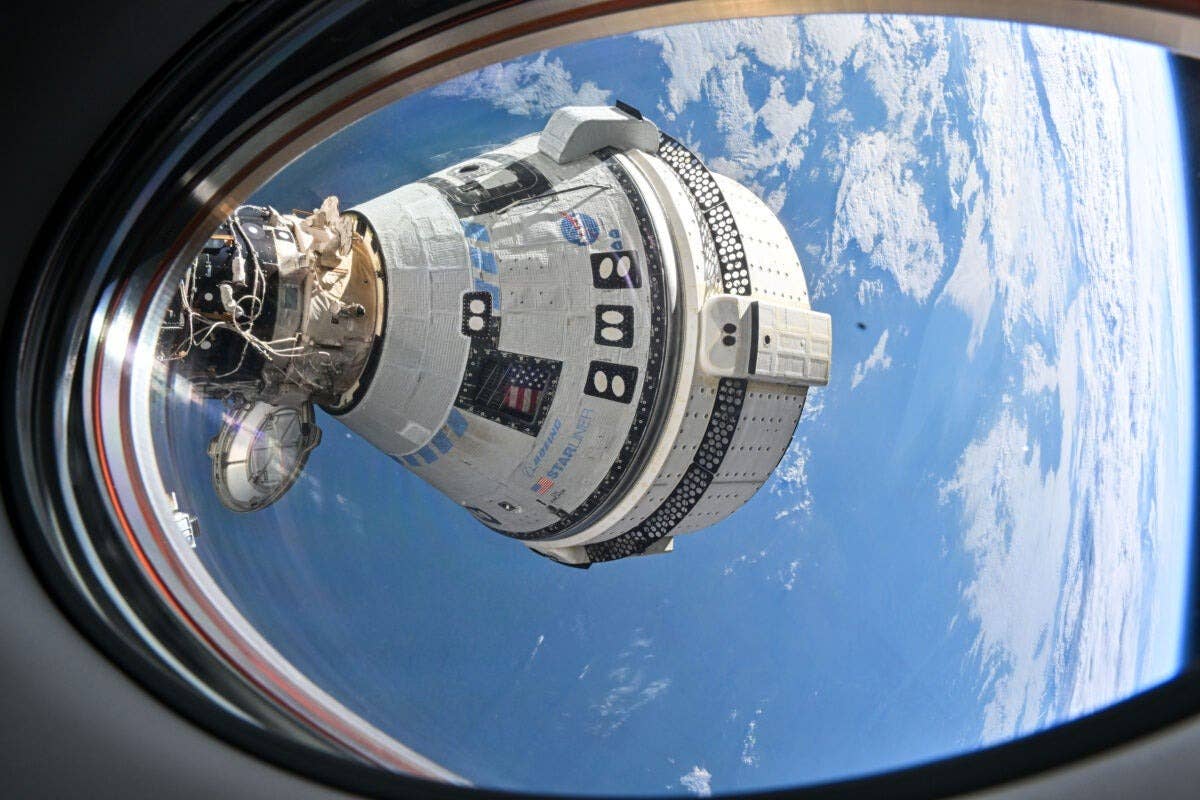

Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule will return from its test flight without a crew. [Credit: NASA]

When NASA announced August 24 that Boeing Starliner astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Suni Williams will remain in space another six months, miss Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's holidays with their families, and land in a different spacecraft, it stirred headlines worldwide.

But theirs is not the first mission to be unexpectedly lengthened or hit by unforeseen circumstances.

What Happened to Boeing Starliner?

Launched on June 5 from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, Starliner’s Crew Flight Test (CFT) sought to evaluate the capabilities of the Boeing-built craft before NASA certifies it for regular International Space Station (ISS) astronaut rotation missions. It was scheduled to spend eight days at the ISS then return Wilmore and Williams to a parachute-aided homecoming in the western United States.

But shortly after liftoff, Starliner suffered multiple helium leaks and reaction control system thruster failures. With several thrusters critically sited on its disposable service module (which will burn up at mission’s end), NASA and Boeing repeatedly extended the flight to perform more tests and gather more data.

Days turned to weeks and weeks became months as testing and data-gathering took place in space and on Earth. The astronauts assessed Starliner’s habitability and functionality. The helium leaks slowly stabilized. And at White Sands in New Mexico, a Starliner thruster was rigorously test-fired to assess its performance and understand possible causes of the thruster failures in orbit.

But it was not enough.

On August 24, NASA opted to return Starliner to Earth empty and keep the astronauts on the ISS until February. In a press conference, Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, said that “the bottom line” was that “there was just too much uncertainty” in how the thrusters would behave. Wilmore and Williams’ homebound ride will instead be SpaceX’s four-seat Dragon Freedom, scheduled to launch on September 24 with two crew members and a pair of empty seats. It is scheduled to return to Earth—with Wilmore and Williams aboard—in February 2025.

Space Ride-Swapping

Over the decades, it has become a common practice for crew to return to Earth in a different spacecraft than the one that took them to space.

The first instance came in January 1969 when, in a bid to grab some of the spotlight from the U.S. Moon-orbiting Apollo 8 weeks earlier, the Soviet Union achieved the first docking of two spacecraft. Soviet cosmonaut Vladimir Shatalov piloted Soyuz 4 to rendezvous with Soyuz 5’s Boris Volynov, Alexei Yeliseyev, and Yevgeni Khrunov. After the two craft docked, Yeliseyev and Khrunov spacewalked over to Soyuz 4 and returned to Earth with Shatalov while Volynov landed alone.

From 1978, cosmonauts routinely swapped Soyuz capsules as visiting crews to the space stations Salyut 6, Salyut 7, and Mir left fresh ships for use by long-duration resident crews, then returned home in older ships approaching the end of their operational lifetimes.

And after 1995, Soyuz cosmonauts began launching or landing on space shuttles and shuttle astronauts via Soyuz. Norm Thagard became the first American to launch and land in different ships—riding a Soyuz to Mir, then landing on space shuttle Atlantis. Between 1997 and 2009, several flyers launched to space on one member of NASA’s shuttle fleet and returned on another.

Stranded by the Shuttle

But missions lengthened by unforeseen factors are rarer.

A notable character at the August 24 Starliner announcement was Ken Bowersox, NASA’s associate administrator for space operations. A former astronaut who flew four shuttle missions and commanded the ISS, he knows a thing or two about getting stranded far from home.

On February 1, 2003, Bowersox was midway through a four-month stint aboard the ISS at the helm of Expedition 6, partnered with Russian cosmonaut Nikolai Budarin and NASA astronaut Don Pettit. The crew planned to return home in mid-March aboard the space shuttle Atlantis. Days earlier, they made a ship-to-ship call with space shuttle Columbia, flying the STS-107 microgravity research mission.

As the ISS flew over Ukraine and Columbia soared high above Brazil, Bowersox and STS-107 commander Rick Husband exchanged pleasantries for a few minutes.

“Glad to see you guys made it into orbit,” said Bowersox.

“We’re really excited to be able to talk to you guys,” replied Husband. “One big space lab to another big old space lab on that beautiful station of yours.”

But Columbia would disintegrate during reentry on February 1, 2003, killing her entire crew, grounding the shuttle fleet and stalling construction of the half-built ISS.

“My first reaction was pure shock,” Bowersox said 11 days later. “I was numb and it was hard to believe what we were experiencing was really happening.”

Mission Control adjusted Expedition 6’s schedule, furnishing the crew some time for reflection.

“When you’re up here for this long, you can’t just bottle up your emotions and focus all of the time,” said Bowersox. “Each of us had a chance to shed some tears.”

With shuttles indefinitely grounded, getting Bowersox’s crew home proved problematic. An unoccupied ISS was hardly ideal but without regular shuttle visits normal operations were untenable. Two-person caretaker crews on six-month tours would keep the station functional until the shuttle returned to flight.

The first such crew arrived in April and Expedition 6 came home on May 6—making Bowersox and Pettit the first Americans to launch on a U.S. shuttle and land in a Russian Soyuz. At 161 days, their tragedy-tinged voyage ran 30 percent longer than planned.

Other Extended Stays

Bowersox and Pettit weren’t the first to experience a significant hike in their mission’s duration.

In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, tanks rumbled into Moscow’s streets and Russia’s tricolor flag replaced the hammer and sickle fluttering over the Kremlin. And two cosmonauts were acutely aware of their once-proud nation’s crumbling future.

One of them, Sergei Krikalev, launched to Mir in May and was due home in October. But with the Baikonur launch base located in Kazakhstan, Russia feared the newly independent Kazakh government might nationalize or refuse access to it.

To placate them, a Kazakh guest cosmonaut was hastily added to the October Soyuz mission, forcing Krikalev to pull a double-length Mir mission of 10 months.

Sergei Krikalev departed Earth a citizen of the Soviet Union and returned to the Russian Federation.

In 1996, NASA’s Shannon Lucid saw her own four-month Mir stay protracted to six months due to shuttle launch delays. Her mission grew from 140 to 188 days, the longest ever flown by a woman. But Lucid also missed her son’s 21st birthday—illustrating spaceflight’s unpredictable impact on families.

Other missions were also lengthened. Notably, in 1998 and 1999 Russian cosmonaut Sergei Avdeyev spent 379 days on Mir—twice his original flight length. And throughout the ISS era, mission failures, changing circumstances and launch delays kept multiple crews in space far longer than intended.

In 2017, a reduced number of Russian cosmonauts on the ISS led NASA to extend astronaut Peggy Whitson’s six-month stay to 9.5 months, a new record for women. And Christina Koch, launched for a six-month stay in early 2019, relinquished her Soyuz return seat that fall to a visiting astronaut from the United Arab Emirates. Koch returned to Earth in early 2020 after 11 months—another record for women.

More recently, in 2021 and 2022 the six-month mission of Mark Vande Hei and Pyotr Dubrov was doubled to 355 days. Vande Hei later remarked that taking care of his mental health proved critically important in getting through the flight.

And across 2022 and 2023, the half-year stay of Russian cosmonauts Sergei Prokopyev and Dmitri Petelin and U.S. astronaut Frank Rubio doubled to 371 days—the first year-plus human space mission of the 21st century. Their lengthy ISS stint arose when a coolant leak rendered their Soyuz capsule unsafe to return to Earth, requiring a replacement ship to be launched to bring them home.

‘Extraordinary Sacrifices’

“Our astronauts,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, “make extraordinary sacrifices away from their homes and loved ones to further discovery.” His rousing words are fittingly apt for Wilmore and Williams as their week-long flight morphs to eight months: the biggest duration hike of any crewed mission in history—a staggering 25 times longer than planned on their day of launch.

Despite immense sacrifices on their families, there can be no doubting Wilmore and Williams’ steely resolve. Having both flown the shuttle and Soyuz, their Starliner launch and Dragon landing jointly will make them the first humans to launch or land in four different spacecraft types. And theirs will sit in the top 20 longest missions ever flown—adding to a corpus of knowledge that someday will get humans to Mars.

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared on Astronomy.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox