Nothing Short of a Fatal Mismatch

A Cessna 140 proved to be a goose among swans in a flock of dedicated STOL.

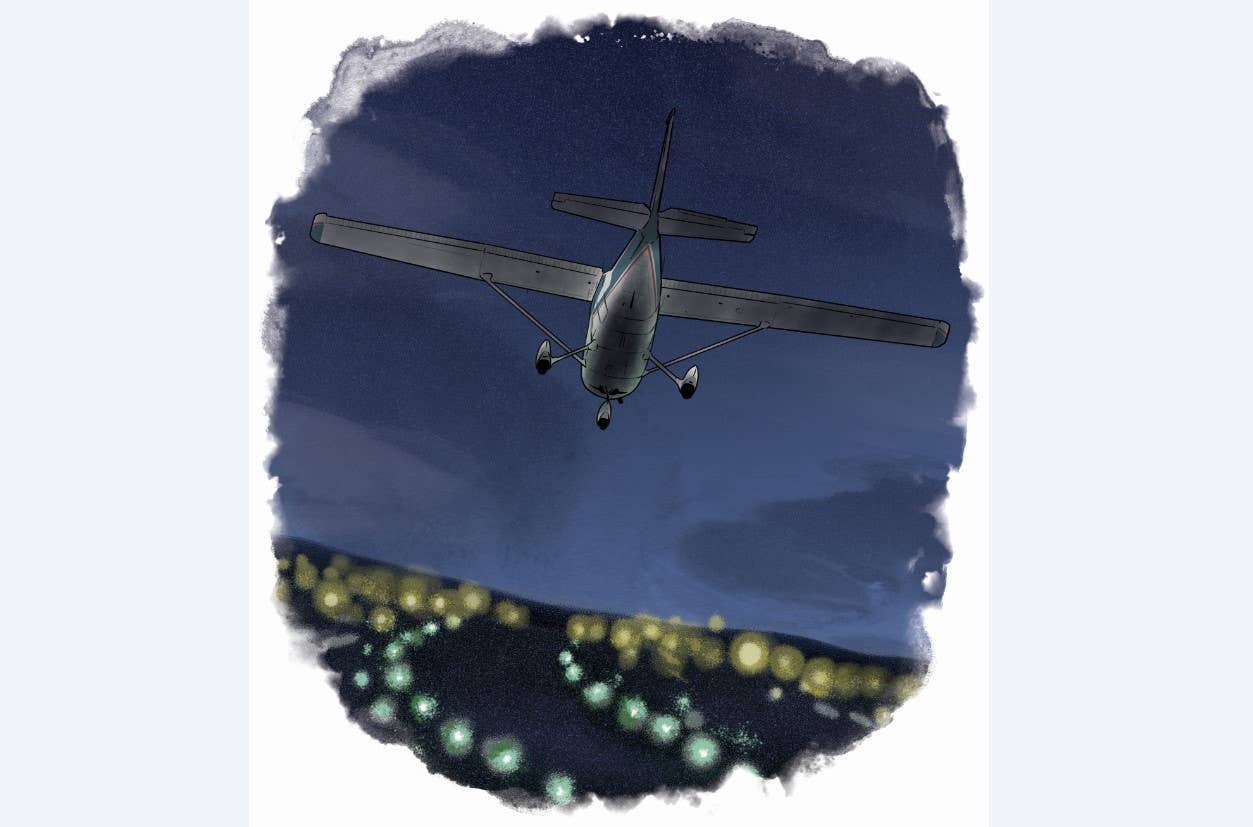

The NTSB blamed a STOL Drag accident in 2022 on the pilot’s obvious ‘exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack.’ [Leonardo Correa Luna]

In May 2022, a STOL Drag event took place at Wayne Municipal Airport/Stan Morris Field, (KLCG) in Nebraska. Training for novices would begin on Thursday and continue into Friday. Qualifying heats would be on Friday afternoon, and the races would continue through the weekend.

The contest, which typically occurs on grass or dirt areas parallel to paved runways, was to take place alongside Runway 5-23.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowOn Friday afternoon the wind picked up. It blew out of the northwest across the STOL Drag course. Qualifying heats were postponed until the next day.

A number of the competitors then decided to conduct an impromptu “traditional STOL” event, omitting the drag racing component. They would use the grass Runway 31, which was conveniently aligned with the wind. The pilots, organizers, and FAA inspectors who were present held a safety briefing, and the participants were divided into four groups of five or six aircraft to prevent clogging the pattern. The objective of the contest was to see who could come to a full stop in the shortest distance after touching down beyond the target line.

Each group completed two circuits without incident. Two groups had completed a third circuit, and now the third group was landing. The third airplane in that group was a modified Rans S-7, the fourth a Zenith STOL 701—unusual among the participants in having tricycle gear—and the last a Cessna 140. The S-7 landed, came to a stop in less than 100 feet, and taxied away. The 701 was still a fair distance out, and the 140 seemingly rather close behind it and low.

- READ MORE: A Cautionary Tale About Pilot Freelancing

A STOL Drag representative who was coordinating the pattern operations radioed the 140 pilot: “Lower your nose. You look slow.” The 140 pilot did not acknowledge. Half a minute later, the coordinator again advised the pilot to lower his nose.

A few seconds later, the 140 yawed to the right, its right wing dropped, and with the awful inevitability of an avalanche or a falling tree, it rolled over into a vertical dive and struck the ground an instant later. A groan went up from the small crowd of onlookers. “Oh, my God, what happened!” one voice exclaimed. What had happened was all too clear—a low-altitude stall-spin that resulted in the pilot’s death.

The 140 pilot, 45, had an estimated 470 hours total time, more than 300 of which were in the 140. He had already qualified for STOL Drag competitions at a previous event.

The wind at the time of the accident was 15 knots gusting to 21. (As with all aviation wind reports, the 15 is the sustained wind and the 21 the maximum observed; no information is provided about lulls or wind speed variations below the sustained value.) The pilot of the 701 said that he had been maintaining about 50 mph (44 knots), as he had on several previous approaches, and that the wind on this approach felt no different than on the others.

The 701 is equipped with full-span leading-edge slats, which make it practically incapable of unexpectedly stalling. Operating at a likely wing loading of less than 7 pounds per square foot, it could probably fly at around 35 mph. For the 701, an approach speed of 50 mph was conservative. The 140’s wing loading was only slightly higher, but its wing was not optimized for extremely slow flight. The 140’s POH stalling speed at gross weight was highly dependent on power setting, ranging from 45 mph power off to 37 mph, flaps down, with full power.

- READ MORE: Two Fatal Cases of the Simply Inexperienced

An FAA inspector who witnessed the accident reported his observations to a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigator. He noted that the 140 generally took longer to get airborne than other airplanes in its group, in part because the pilot, after first lifting the tail, rotated prematurely, so that the tailwheel struck the ground and the airplane continued rolling for some distance before finally becoming airborne. The pilot, he said, would climb steeply at first, but then have to lower the nose to gain speed. He appeared low and close behind the 701 on the last approach.

Earlier videos also showed that, on landing, the 140 rolled farther than other contestants, despite braking to the point of almost nosing over.

On previous circuits the pilot had used flaps, but on his last approach he failed to put the flaps down. The omission could account for the coordinator’s observation that the nose seemed high. Full flaps would have resulted in a more nose-low attitude.

The NTSB blamed the accident on the pilot’s obvious “exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack.” It went on to cite as a contributing factor the “competitive environment, which likely influenced the pilot’s approach speed.” Since there were many knowledgeable observers of both the accident and of several previous takeoffs and landings by the 140, and everything was recorded on video from several angles, the NTSB’s diagnosis could probably have been even more specific and mentioned the failure to use flaps and the premature downwind-to-base turn.

If, by a chance misjudgment, the 140 pilot found himself too close behind the 701, he still had options other than slowing to the lowest possible speed. Since there was no one behind him, he could have gone around or made a 360 on final. The aircraft waiting to take off would have had to stand by a little longer, but only a fool would grumble because another pilot was being wisely cautious.

Instead, the 140 pilot chose to maintain his spacing by flying as slow as he could.

The decisive factor in the accident was most probably the failure to use flaps. It was almost certainly inadvertent. He probably forgot to put the flaps down, then believed they were down—because he had them down on the previous circuits—and chose his speeds accordingly. Adding flaps would have brought the stalling speed down 3-4 mph and also obliged him to use a little more power. Actually, it would have been quite a bit more because he was low, and the added power would have given him still more cushion.

The 140 was a goose among swans in this flock of dedicated STOL airplanes that possessed a near-magical ability to take off and land in practically no distance at all. Still, it was OK to be an outlier. The point of the contest was to have fun. You didn’t need to go home with a trophy—not that there even was one for this impromptu event.

But integrating an airplane with somewhat limited capabilities among more capable ones required special attention to speed and spacing. It would be easy to make a mistake. Once the mistake was made, and compounded by the failure to use flaps, all the pilot had left to lean on was luck—or willingness to recognize an error and go around while there was still airspeed and altitude to recover.

Note: This article is based on the National Transportation Safety Board’s report of the accident and is intended to bring the issues raised to our readers’ attention. It is not intended to judge or reach any definitive conclusions about the ability or capacity of any person, living or dead, or any aircraft or accessory.

This column first appeared in the July/August Issue 949 of the FLYING print edition.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox