If the San Carlos tower controller hadn’t cleared me for a direct base entry, I would have declared an emergency, but he did. Barry Ross

Every summer for several years, I have been flying my Varga from my home base about 25 miles south of San Francisco—San Carlos, California—to Ashland, Oregon, to take in a play at the Shakespeare Festival and then proceed to Idaho for some camping.

The Varga is a low-wing, two-place, tandem-seat airplane with a 150 hp Lycoming—sort of a poor man’s T-6 but with tricycle gear. Like many aircraft manufactured outside of the “Big Three” (Cessna, Piper, Beech), it has a checkered history. It was designed by Douglas Aircraft Company’s chief test pilot, William Morrisey, who manufactured a few bearing his name. Then Shinn Engineering took over, and a few more were built under that name. Finally, George Varga acquired the tooling and type certificate, and production really got underway in Chandler, Arizona. More than 150 were produced in all.

Getting back to our story, Ashland is a pretty little college town situated in a valley just over the California-Oregon state line. The Shakespeare Festival is produced by a professional theatrical group founded in the 1930s by Angus Bowmer. No small-time amateur operation, this is the real thing. Stacy Keach played here early in his career, and Dick Cavett put in a summer as a spear carrier in various plays. There’s an indoor theater for matinees and an elaborate outdoor Elizabethan theater where evening performances take place.

After flying in on a late afternoon for one of my visits, refueling and tying down, I cadged a ride to town with an ex-United Airlines pilot who had retired with seniority number 9. This was a lucky break—usually, I had to walk the 2 or 3 miles, with a refreshment stop along the way. After hanging about, killing time until dark, I took my reserved seat for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. After that most excellent entertainment, I had a late dinner and took a taxi back to the airport, where I broke out the air mattress and sleeping bag from my camping gear and sacked out under the Varga’s wing. Awakened by sunrise the next morning, I drank my thermos of coffee and took off. Destination: Smiley Creek, Idaho.

More than a matter of the distance covered, this was a transition from high culture to barren wilderness. Located about 50 miles north of Sun Valley, at an elevation of more than 7,000 feet, Smiley Creek was the jumping-off point for a return-to-nature sojourn. With my backpack buckled on, I hiked a couple of miles and another thousand feet of elevation farther up into the Sawtooth Mountains: a place so pristine, the water in the streams can be potable without purification. Here, I communed with nature for a full week, living on freeze-dried food, a jug of wine and a couple books. After seven days of this idyll, I emerged unshaven and unwashed (a shallow icy stream is a poor substitute for a bathtub). Camping gear stashed in the airplane, I had a bite to eat at the lunch counter/general store across from the airport. Then I made a high-altitude, grass-strip takeoff for the short flight to Hailey, Idaho, to gas up and head for home.

Read More: I Learned About Flying From That

Lovelock, Nevada, has always been my refueling stop on the way home because it’s at approximately the halfway point, and the avgas, sold by a flying club, is relatively inexpensive. But on this trip, the usual prevailing westerly wind was absent, so I still had more than half of my fuel remaining when I arrived overhead Lovelock. Because landing there would involve descending down into the hot—probably bumpy—air and then climbing again to clear the Sierra Nevada mountains, I elected to bypass it and refuel somewhere farther along. After all, the Sacramento Valley ahead was practically wall-to-wall airports. Not to worry. With plenty of airports to choose from, I saw no need to decide on one; I would just play it by ear.

A little later, I was over the Sacramento Valley, and the fuel supply was still comfortable. Because of the shape of the tanks, the movement of the fuel-quantity indicator tends to speed up as the tanks empty. I was aware of this characteristic but hadn’t planned ahead for it. There’s a temptation, when running low on fuel, to speed up in order to make the airport before running out of fuel. That would be nonsensical; the proper course of action would be to slow to best lift-over-drag speed, where the aircraft is at its most efficient. I didn’t do either but proceeded anxiously over the short distance remaining.

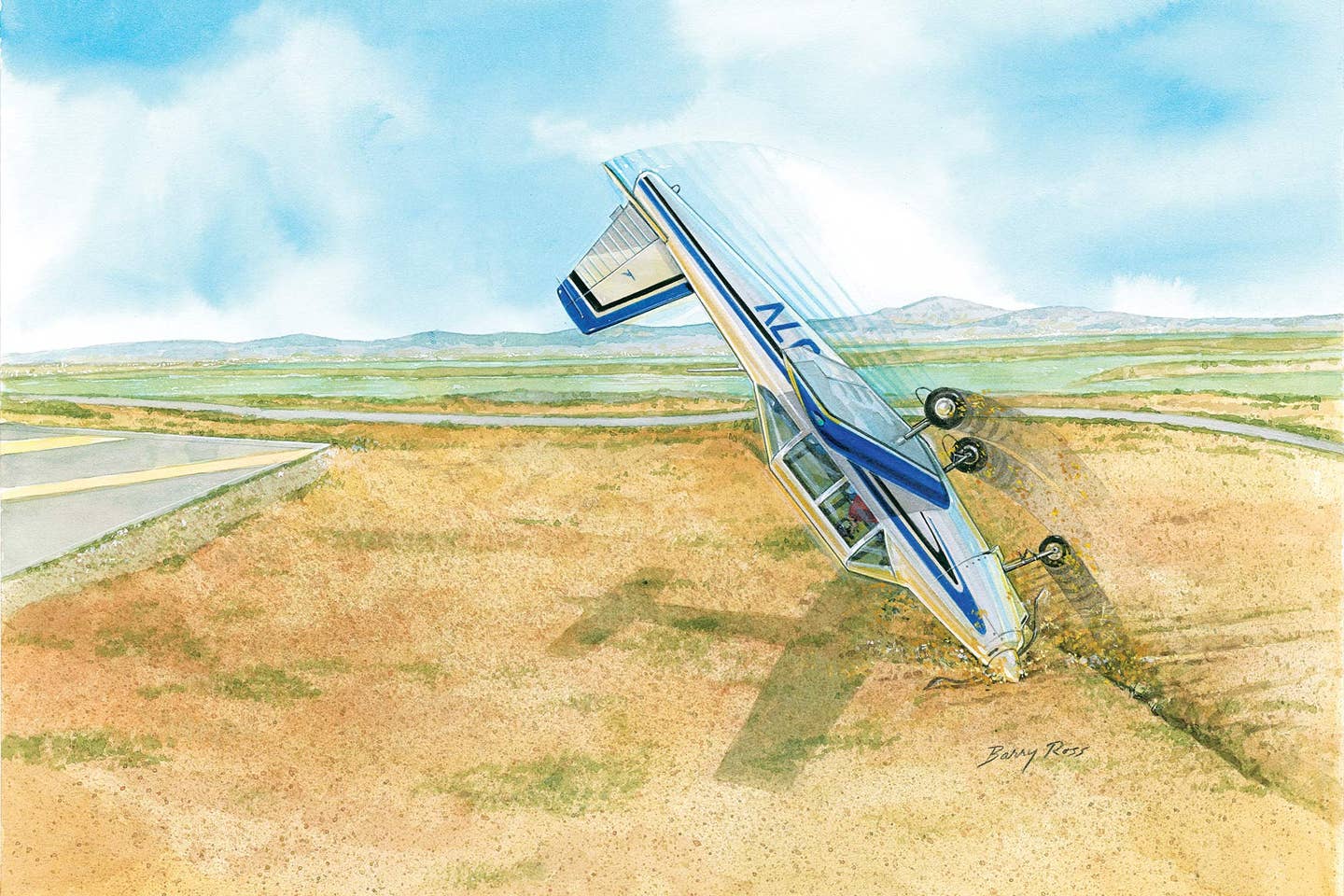

If the San Carlos tower controller hadn’t cleared me for a direct base entry, I would have declared an emergency, but he did. When the engine quit at 400 feet on short final, I wondered if I would have enough momentum to clear the runway. My bemusement was short-lived, however, as the enormous speed-brake effect of the windmilling propeller set in. Flying with a windmilling propeller is something that most pilots rarely practice—so it comes as quite a surprise when it is encountered. I know that a stationary prop has less drag than a windmilling one, but I wasn’t about to slow to a near stall at 400 feet. I touched down about 100 yards short of the runway, hit a ditch and flipped inverted. I was uninjured, but the Varga was extensively damaged. It flew again after about a year and the expenditure of vast sums of money.

It’s easy for second-guessers, myself included, to speculate that a base flown closer in would have saved the day. But this presumes either prescience or a lucky break because it only shifts the margin of error from too low to too high, from where an overshoot might have been unavoidable and a go-around out of the question. And it misses the point—that a fuel stop alone would have prevented my accident.

This story appeared in the June/July 2020 issue of Flying Magazine

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox